Tom G. Wolf / September 10, 2018

John Wayne Gacy exhibit at the National Museum Of Crime And Punishment, Washington, D.C. Photo: m01229/Flickr

Serial killers exert a peculiar hold over many among the general public. Their crimes are appalling, yet fascinating; their motives are frequently incomprehensible, sometimes even to the killers themselves. Yet people find themselves drawn back again and again to these seemingly complex characters and the gruesome nature of their crimes. Writing for Psychology Today, Professor Scott Bonn noted that: “In many ways, serial killers are for adults what monster movies are for children—that is, scary fun! However, the pleasure an adult receives from watching serial killers can be difficult to admit, and may even trigger feelings of guilt.”

It’s difficult to pinpoint the true birth of true crime as a genre. One could point as far back as writers from Ancient Rome like Suetonius, who documented the horrors of rulers like Caligula and Nero in garish fashion. German pamphlets circulating in the 1400s documented the monstrous impalings of Vlad Țepeș, complete with woodcut illustrations. More recently, we see the coverage of Jack the Ripper’s crimes in Victorian-era newspapers, and author Joyce Carol Oates cites the influence of William Roughead, an amateur criminologist who wrote about virtually every high profile murder to occur in Scotland between 1889 and 1949. And of course, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1966) cannot be underestimated.

But it’s fair to say that the most significant influence on the modern incarnation of true crime was the book Helter Skelter, originally published in 1974. Relaying the story of the Manson family, it differentiated itself from its competitors by being co-written by Vincent Bugliosi Jr, who had been the lead prosecutor on the infamous case. It was an instant success, and naturally sparked a host of imitators. In the years since its publication, it’s been accused of being sensationalist and inaccurate, yet it remains a classic of the true crime genre and continues to sell well to this day.

Whichever way you slice it, it’s apparent that we are attracted to the grim and macabre. Yet there may be a more sinister side to this fascination. Questions about the true crime industry’s complicity in the stoking and reinforcing of dark desires in the vulnerable have often been raised. While the factors driving people to commit murder are complex—and beyond the scope of this article, to be frank—there’s no question that real-life serial killers have drawn inspiration from their forebears. True crime magazines were found among the many gruesome souvenirs found at Ed Gein’s farm. Dennis Rader explicitly claimed that discovering the work of Harvey Glatman—the so-called “Glamour Girl Killer”—in one of his father’s true crime magazines directly inspired his later exploits. As his execution drew close, Ted Bundy also claimed that salacious true crime stories and pornography had inspired him to a career of violence, rape, and murder.

Of course, it should also be noted that the vast majority of people who enjoy true crime-related media do not go on to participate in crime themselves. In Bundy’s case in particular, it’s hard not to wonder whether he was having one last joke at the expense of noted moral crusader and Focus on the Family founder Dr. James Dobson. Nonetheless, the proliferation of real and fictional serial killers alike in pop culture is testament that we don’t feel too guilty. True crime media has become an enormous industry, with books, documentaries, podcasts, music, board games, trading cards, and websites providing a plethora of material amounting to a macabre fandom. These items can even extend to one’s fashion choices—a quick look online will reveal plenty of t-shirts, buttons, and patches emblazoned with the likes of Charles Manson, Jeffrey Dahmer, and Ed Gein.

A Collection to Die For

For most true crime aficionados, the occasional book or TV show is more than enough to satisfy the psychological itch. But there exists a subset of less conventional merchandise that has gained a foothold among the more extreme fans—murderabilia. The expression was originally coined by Andy Kahan, director of the Houston-based Mayor’s Crime Victims Office—and anti-murderabilia campaigner—to refer to items that had belonged to or were created by serial killers, murderers, or other perpetrators of violent crime: clothing, personal effects, artwork, photos, music—sometimes even the murder weapons themselves. However, it’s since evolved into a broader term that refers more generally to items connected with convicted criminals; a more innocuous example might include letters from Martha Stewart’s time in prison.

For most true crime aficionados, the occasional book or TV show is more than enough to satisfy the psychological itch. But there exists a subset of less conventional merchandise that has gained a foothold among the more extreme fans—murderabilia. The expression was originally coined by Andy Kahan, director of the Houston-based Mayor’s Crime Victims Office—and anti-murderabilia campaigner—to refer to items that had belonged to or were created by serial killers, murderers, or other perpetrators of violent crime: clothing, personal effects, artwork, photos, music—sometimes even the murder weapons themselves. However, it’s since evolved into a broader term that refers more generally to items connected with convicted criminals; a more innocuous example might include letters from Martha Stewart’s time in prison.

The reasons behind purchasing murderabilia vary widely, just as with any other hobby. Some people collect out of historical interest, some see it as a natural extension of their interest in true crime, while others may see it as a way of keeping controversial artifacts out of the public eye. And, of course, some collectors just get a kick out of owning something attached to a dark history.

It’s an industry with a history much longer than its name; indeed, you could even argue it dates back to ancient occult traditions such as the Hand of Glory, which involved the possession of parts of executed criminals. The Renaissance Europe tradition of the Wunderkammer could also share some overlap, depending on the individual’s collection. In the twentieth century, one cannot overlook the importance of carnival sideshows, where true crime-related artifacts—occasionally even human remains—could be viewed by a gawking public. All for a fee, naturally.

A high-profile example would be Ed Gein’s car (the name of an ’80s punk band, naturally), which was exhibited for a time after his imprisonment. Bunny Gibbons—a carnival sideshow operator from Illinois—purchased Gein’s vehicle at an auction in 1958, and swiftly realized its exhibition potential. Attendees could pay 25 cents to have their photo taken alongside the 1949 Ford Sedan, which must have made for a memorable souvenir of a day at the fair. After initially attracting thousands of viewers, public outcry eventually shut the exhibit down, with Gibbons himself disappearing into obscurity shortly afterwards.

To really get an understanding of how the modern murderabilia industry arose, we need to take a look back at one of the twentieth century’s most notorious serial murderers—John Wayne Gacy.

Pogo the Clown

John Wayne Gacy’s crimes have been recounted exhaustively elsewhere, so it seems redundant to delve into all of the gory details here. In short, he was a serial killer, rapist, and pedophile who preyed on young men and teenage boys. By day, Gacy was viewed as an upstanding pillar of the community: a successful business owner and a prominent member of the local chapter of the Jaycees. It was a position he leveraged to prey on his preferred victims, most of whose bodies were hidden beneath Gacy’s suburban home in Cook County, Illinois. Fortunately, the killing came to an end in 1978, when he was linked to the disappearance of 15-year-old Robert Piest. An investigation quickly revealed the true extent of the horrors that lay in his basement, and Gacy quickly turned himself in. Always fond of blackly comic jokes, Gacy infamously claimed that he was only guilty of “running a cemetery without a license.”

Gacy’s high body count and sexual proclivities have always marked him out as a disturbing figure among serial killers. But there are two additional footnotes that have made him a particularly menacing figure. The first is his predilection for dressing as a clown—“Pogo,” as he referred to himself. Numerous photos of him in costume are extant, disconcerting in their own right, even without context. More disturbing is that he was often booked to perform at neighborhood parties for children. The second is his art, which inadvertently helped spawn the modern murderabilia industry. While in prison, Gacy began to paint to pass the time. His works had a naïve, crude folk-art quality to them; they are instantly recognizable, even after seeing just a few pieces.

Harold Piest, the father of one of John Wayne Gacy’s victims, throws a piece of Gacy’s artwork onto the bonfire in Naperville, Illinois, June 18, 1994. Photo: AP Photo/Frank Polich

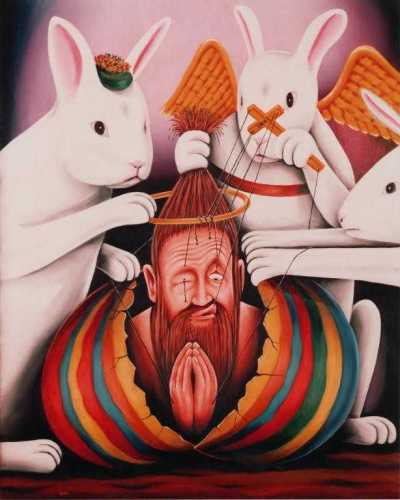

Yet for all his technical limitations, Gacy’s subject matter was diverse—Disney characters, baseball, skulls comprised of nude bodies, G.G. Allin, and fellow criminals like Charles Manson and Ed Gein. A couple of his works even depict another famous killer clown—Pennywise, the titular monster of Stephen King’s It (1986). But of his surviving works, his most notorious are his self-portraits. Generally depicted in full Pogo the Clown garb, Gacy cuts a deeply unsettling figure, the primitive strokes belying the horrible truth behind the august face.

In truth, none of the paintings would be of much interest to the wider public were it not for their notorious creator, à la Hitler’s watercolor images. Still, given his notoriety, unusual style, and frequently unsettling subject matter, his work swiftly attracted interest from the outside world. Gacy began to forge something of a cottage industry out of his works, taking commissions from his jail cell. He was allowed to earn money from these paintings until the mid-80s, when new laws were enacted to prevent both him and copycat aspiring artists. Given the continued proliferation of his art, this measure seems to have been wholly ineffective.

Most of the early deals appear to have been brokered by Stephen Koschal, who got the job simply by writing Gacy in prison. A memorabilia dealer who estimates he sold around 150 of Gacy’s works over a number of years, he’s a highly divisive figure. Most famously, he convinced a number of Hall of Fame baseball players to sign a painting of Gacy’s, which depicted the Chicago Cubs playing against the Seven Dwarves. The players were not aware of the identity of the artist.

As might be expected, Gacy’s newfound career as an artist inspired no small degree of anger from victim’s rights groups and the wider public. Shortly after his execution, businessman Joseph Roth and Walter Knoebel spent more than $10,000 on various Gacy works and paraphernalia, burning it in a public bonfire—a display of catharsis for victims and the city of Chicago alike. Yet the gesture seems to have had little long-term impact; huge amounts of Gacy’s work are still extant. Collections of his work are periodically made available for sale to the public, while others trade behind the closed doors of the private market. Intentionally or not, the Killer Clown helped showcase just how lucrative the murderabilia industry could be, for inmates and private sellers alike.

(Not) Dead and Buried

In retrospect, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Gacy’s artistic “success” would inspire greater interest in the creative output of other controversial figures. Charles Manson’s songs, Henry Lee Lucas’s paintings, Issei Sagawa’s restaurant reviews and books, and many more. Among the most notable is Dr. Jack Kevorkian; the notoriety surrounding the man both before and after his convictions has led to increased interest in both his paintings and his music. Kevorkian’s works are far more technically sophisticated—if decidedly unsubtle in their imagery—though presumably Kevorkian also had access to better supplies, since he wasn’t painting from behind bars.

The scope of products available has expanded greatly, too. While objects like clothing, books, letters, photos, paintings, and music make some degree of conventional sense, some entrepreneurial inmates have managed to sell objects as arcane as their own fingernail clippings. One might even argue that it’s a warped continuation of the collection of saint’s relics—which was in itself quite a profitable enterprise for the Catholic Church, once upon a time.

Yet the creation and sale of murderabilia hasn’t gone unchallenged. Even before Gacy, lawmakers had recognized the potential for such an industry. In 1977, New York State passed a law in the wake of the capture of David Berkowitz (the Son of Sam killer) aiming to prevent criminals profiting from their notoriety, primarily through book deals. It yielded mixed results; in 1991, the law was eventually overturned as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, due to a lawsuit brought by Simon & Schuster. The ruling found that:

The New York law is not narrowly tailored to achieve the State’s objective of compensating victims from the profits of crime. The law is significantly overinclusive, since it applies to works on any subject provided that they express the author’s thoughts or recollections about his crime, however tangentially or incidentally, and since its broad definition of ‘person convicted of a crime’ enables the Board to escrow the income of an author who admits in his work to having committed a crime, whether or not he was ever actually accused or convicted.

“Son of Sam Law” continues to be a moniker applied to any law, rule, or clause that aims to prevent profiting from crime. As might be expected, newer laws have tended to attempt to target the manufacture and sale of murderabilia, rather than simply setting their sights on book sales. eBay has banned murderabilia from its site since 2001, and a number of US States have taken similar steps, including Texas, California, New Jersey, Michigan, and Utah.

Understandably, murderabilia remains a controversial industry, yet it continues to flourish in a reasonably open fashion via sites like Supernaught, Serial Killers Ink, and Murder Auction. The sale of high profile items periodically makes its way into the mainstream media, too. In 2016, George Zimmerman sold the gun he used to shoot Trayvon Martin for $250,000. Given that he was acquitted of any crime, it may not technically be murderabilia, but it’s hard to see it as anything else.

The impact on wider pop culture and smaller subcultures alike can’t be discounted, either. Hollywood luminaries John Waters and Johnny Depp expressed admiration for Gacy’s art during an interview in 2014. Jonathan Davis, lead singer of Korn, was also a murderabilia collector at one point, even planning to open a true crime museum. Guitarist Dave Navarro claims to own a number of Gacy’s works, one of them apparently gifted by Marilyn Manson. Metal band Acid Bath used one of Gacy’s “Pogo” self-portraits on the cover of their 1994 debut When the Kite String Pops. Never ones to shy away from controversy, their 1996 follow-up, Paegan Terrorism Tactics, would use the painting “For He is Raised” by Jack Kevorkian.

It seems likely that murderabilia will continue to exist in one form or another indefinitely, though the means of distribution may change and the debate around its ethics is likely to be a permanent fixture. It’s tempting to see interest in murderabilia as some kind of anomaly, an aberrant behavior limited to the deeply disturbed. Yet this clearly isn’t the case. As with other forms of true crime media, murderabilia collectors need not necessarily be more unusual than anyone else—though they may have deeper pockets. In a country that has repeatedly shown that it values the right to bear arms above the rights of its citizens to life and the pursuit of happiness, isn’t murderabilia simply a natural outcome?

Whatever the individual convictions of the reader, it must be admitted that it’s an unfortunate side effect of human memory that murderous perpetrators tend to be far better remembered than their victims. Many people with even a passing familiarity with true crime could probably give you a rundown of John Wayne Gacy’s atrocities—but how many could name even one of the people buried beneath his house?

Victim’s rights advocates contend that the ongoing sale of murderabilia glorifies horrific crimes and causes surviving family members undue pain. Yet the issue is not so cut and dried. Here, the murky waters of what constitutes freedom of speech and expression versus protecting the interests of victims and their families reach a confluence. The United States has a robust tradition of protecting freedom of speech, and that includes a certain degree of freedom to offend. An outright ban is unlikely to ever occur, simply because it would potentially infringe on a host of other rights in the process—controversial gore and true crime websites such as Rotten.com and Ogrish thrived on such legal ambiguity for years.

Gacy himself was executed by lethal injection in 1994, unrepentant to the last, his final words a defiant “Kiss my ass.” His posthumous celebrity—and the subsequent legal wrangling surrounding it—would have probably been a source of great amusement to him.

Tom G. Wolf is a Sydney-based writer who is a keen fan of horror films, heavy metal, and cats. You c an read more from him at Lupine Book Club.

an read more from him at Lupine Book Club.

They should not have lived long enough to complete a painting. Dilemma solved.

“Whichever way you slice it” -ha. ha! Very interesting story. I’ve always wondered about these women who “fall in love” with some of these psychopaths in prison. Is there something psychologically wrong with them Maybe that can be your next subject.

There’s a name for that: hybristophillia. There are a number of theories as to what causes it, ranging from an evolutionary need for a “strong and powerful” partner, the belief that a violent lover can be changed through love or that there’s a good person in there, to a desire to control their lover by having one that won’t go anywhere or see anyone else (aka someone in a prison or mental institution). It’s going to show up in a story I write one of these days, I’m sure of it.

This desire to see, touch, or own a piece of a serial killer’s life definitely touches on our obsessions with celebrity and collecting. I think the deeper fascination with killers or murder in general satifys some hardwired human instinct. As was mentioned, it is fun to be scared and so, it becomes fun to learn about these horrible, terrifying murderers from a safe distance while they are incarcerated or already long-passed.

Fascinating article. Raise some serious questions about what to do with these artefacts and the morality of collecting

Thanks Charlie! Yes, a difficult question — though like I said in the article, a total ban seems unlikely. It probably wouldn’t be very effective anyway, looking at how they tried to stop Gacy in the mid-80s.

Nice article. I do think though that serial murderers are physically attracted to the porn, etc., rather than the porn affecting them. An exception would be the school shooters and other one-time killers who seem to grow sick of their own selves and commit suicide as an out. I have heard Ted Bundy’s first defining act was at about 7 years old, when he took a bunch of knives from the kitchen and placed the sharp knives in a circle around his aunt while she was sleeping. He stuck around to see her reaction.

Thanks Donald, glad you enjoyed the read. It’s not a topic I feel I can draw any grand conclusions around, but many serial killers *do* seem eager to blame anyone or anything aside from themselves. It can be quite a calculated exercise in securing a reduced sentence.

I think for some people, it’s like enjoying horror stories: we like getting scared, and sometimes we’ll collect representations of horror movies or books that scare us or that we found memorable. I actually own a couple of items related to Jason Voorhees, and I have a poster from last year’s IT in my living room. For murderabilia, it may be that the fact that the items aren’t fictional adds an extra layer and makes them more desirable to some people.

Yes, I have a ton of horror memorabilia around the house — t-shirts, action figures, posters etc. With that said, I like these things explicitly because they are *not* real; Hellraiser is a wonderful film full of graphic gore, but it is also a million miles away from a real crime scene photo. But for some people I suppose murderabilia is the next logical step up from horror to prove how edgy they are, just like the older kids in high school who used to boast about looking at Rotten.com or similar.

Others have a genuine interest in outsider art and see it as historically important, which I suppose is fair too. I really don’t know where I sit on the industry as a whole, but I personally couldn’t see myself buying Gacy’s work because of the human cost. And to be fair, while the article focuses on the more gruesome stuff, there’s plenty of innocuous things on the market too — for a while you could buy Martha Stewart’s prison letters, which is an interesting study on the subject itself. As a prisoner she was only particularly interesting because she was already so famous!

That’s very true.

Just one question: who would want to own Martha Stewart’s prison letters? Sounds pretty boring, relatively speaking.

Haha! A very fair question. Not something really to my taste either, but such is the cult of celebrity. Imagine if one of the Kardashians went to jail!

I’d tell the warden they could keep them and they should take the rest of the family as well.

I think some people do it for their own interests that are masked. Total madness!

There are hypotheses about the inherently violent nature of humans and other animals. Whether it’s related to the need for lethal forces to survive and mate (implying a phylogenetic component), is still fiercely debated. Some researchers have even gone to the extent of saying that humans are the most violent among all mammals. (https://www.nature.com/articles/nature19758). This something worth considering, especially in view of lower crime rates in countries where the law is strictly imposed. This implies that societies modify our innate tendencies. Rates of homicide in modern societies that have police forces, legal systems, prisons and strong cultural attitudes that reject violence are, at less than 1 in 10,000 deaths (or 0.01%). Children and adolescents have violent tendencies; most parents have been upset by some form of childhood cruelty to animals – whether it’s pulling the legs off of a bug or sitting on top of a puppy. I guess we are social animals, who are brought up in civil environments. This will explain why some people have a certain longing for violent personalities.

Yes, it is an interesting question. I don’t have any firm answers there; I’m just an interested party and very far from an expert. I agree that there are likely tendencies in many people that are modified via culture/laws/religious influence, preventing them from doing something considered bad or evil.

Whether we could all be like Gacy, I’m not so sure — people like Gacy and Dahmer et al appear to be operating on an entirely different wavelength. When they are finally caught and explain their motives, they are often nonsensical or far too “simple” to explain such horrors to more conventional minds. What troubles me more is wondering how many potential Gacys who haven’t done anything yet but are just a step or two away from taking the plunge.

I think of the serial killer influence in music. I must say that Volbeat took the side of the victim in “Mary Jane Kelly” instead of the killer. Would be nice to see more of that. I enjoyed your info:)

Thanks Michelle! Yes, it’s something not seen very often — especially in metal. People tend to go the Cannibal Corpse path, partly because of genre conventions and partly because it’s easier, I think.

This reminds me of the time I bought a pair of novelty earrings with that famous photo of Jeffrey Dahmer standing up in court. I gave them to my friend as a gift, as we’d both spent our twenties watching horror movie after horror movie together – I thought they were funny and that she’d get a kick out of them. Now though, I’m wondering just why you’d wear something like that when real people were killed… but yeah, I never saw those earrings again, lol; I think she probably tossed them, and probably fa good call too..

Yes, I wonder about this too. There are a couple of novelty shirts I’ve almost bought for family/friends/myself, but there is a real human cost that is often overlooked. It’s interesting how things may change over time though — as someone who’s spent most of their teen and adult life involved in metal culture, it’s amazing how many Vlad the Impaler shirts you see doing the rounds. A few hundred years from now some of these people will, for better or worse, be folk icons if they’re not already.

Ugh, that final Ted Bundy interview. It turned my mom into a militant anti-porn crusader and led to multiple freakouts about my inevitable evolution into a serial killer after some hustler magazines were discovered hidden in my bedroom.

Pingback: “To Witness the Final Moment”: 40 Years of ‘Faces of Death’