By Richard McKenna / May 6, 2024

Of all the visionary artists to emerge from the illustration boom of the ’60s and ’70s, Bob Fowke must be one of the most unfairly neglected.

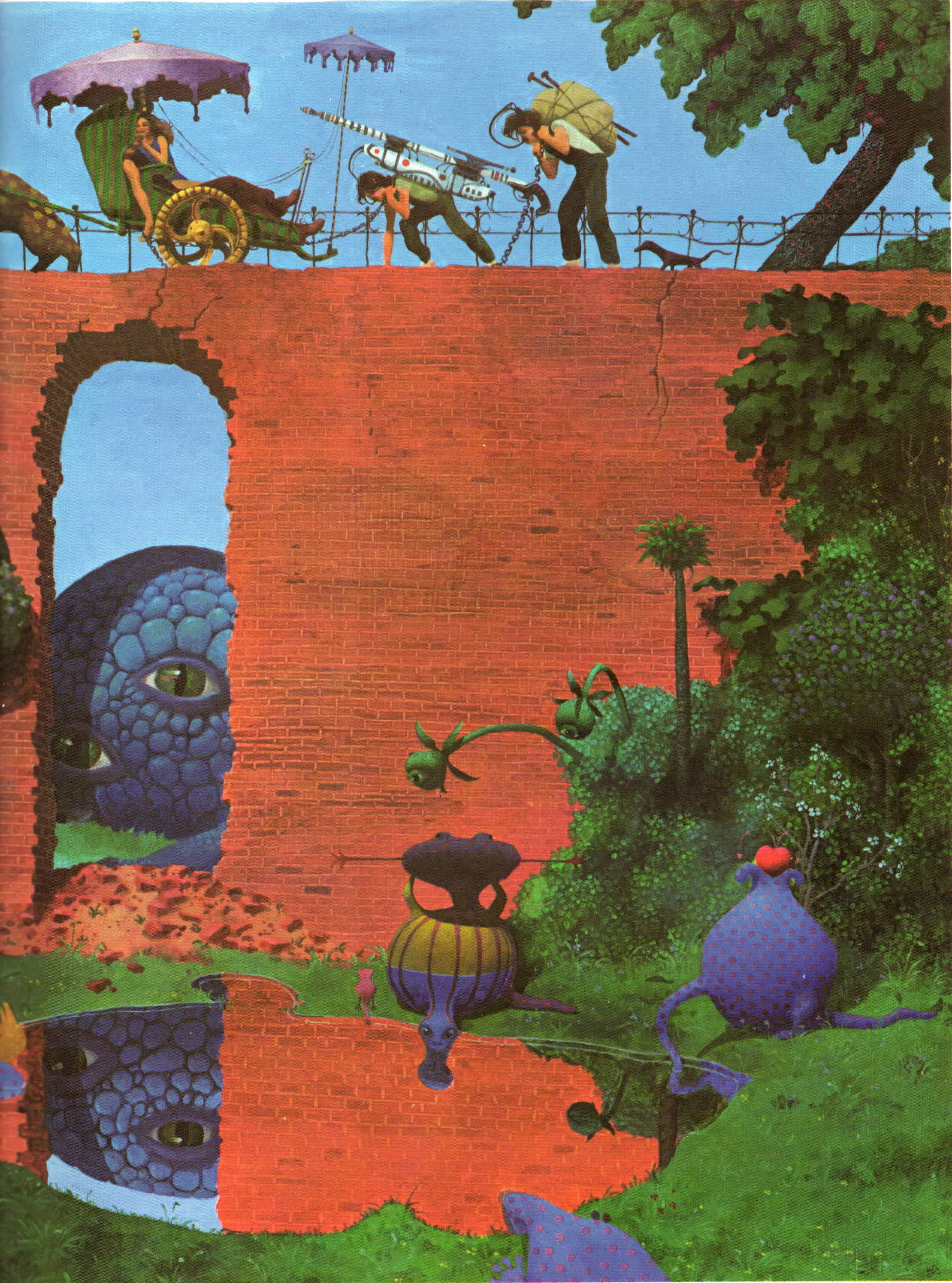

I first became aware of his idiosyncratic visions through his covers for Sci-Fi 1, 2 and 3, anthologies of specially commissioned science fiction stories for young children published by Armada books in the mid-’70s. To an extremely literal-minded (though people who knew youthful me might say simple-minded) child like myself, obsessed with very literal-minded depictions of spaceships and alien worlds, Fowke’s pictures hit me like a bucketful of acid dumped into the South Yorkshire water supply. Beguilingly tactile and alluring with their bright colors and odd forms and technologies, they were at the same time worryingly surreal, seemingly communicating things that they weren’t overtly saying.

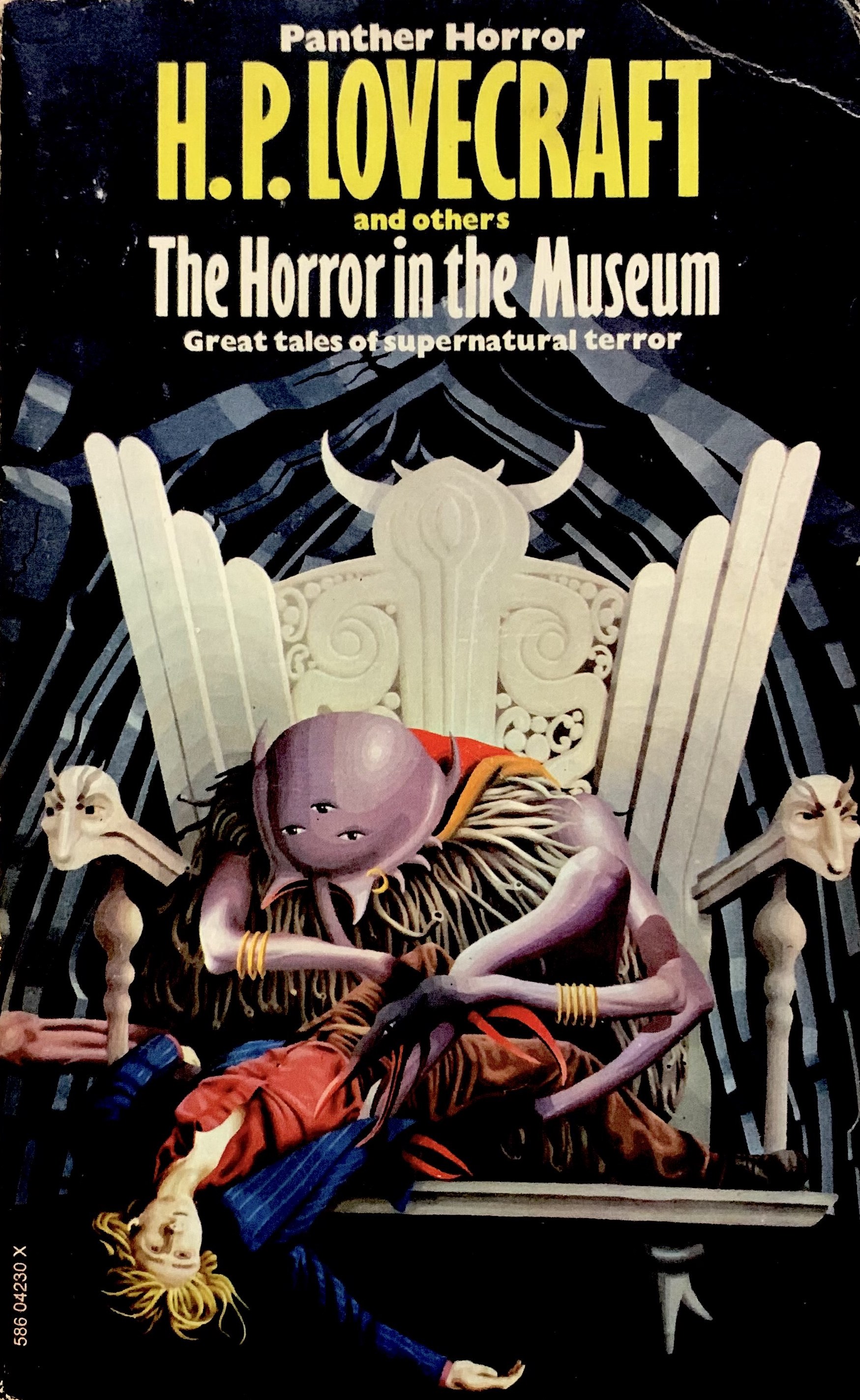

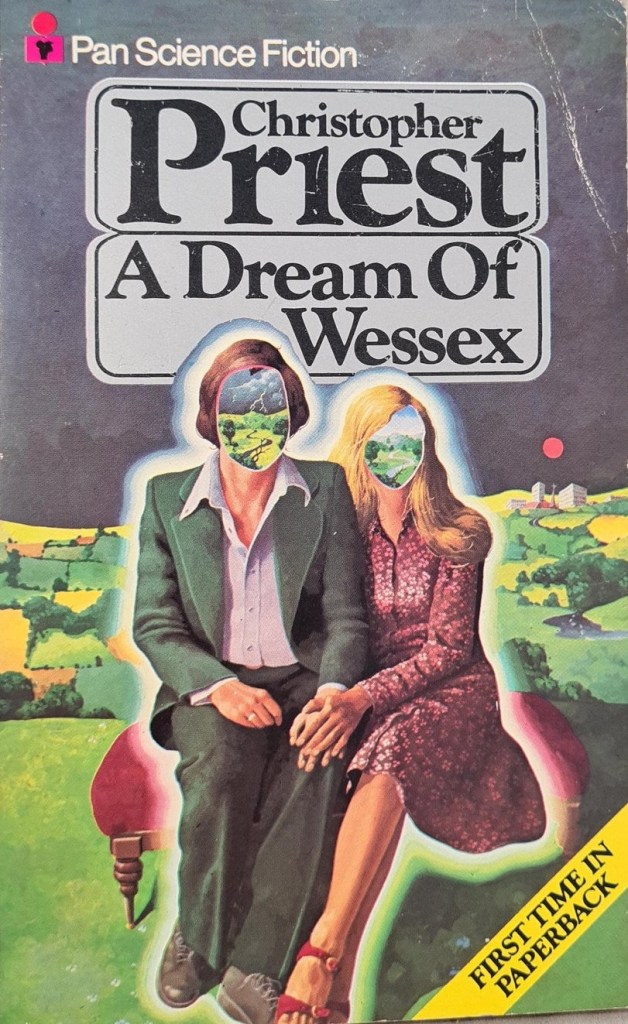

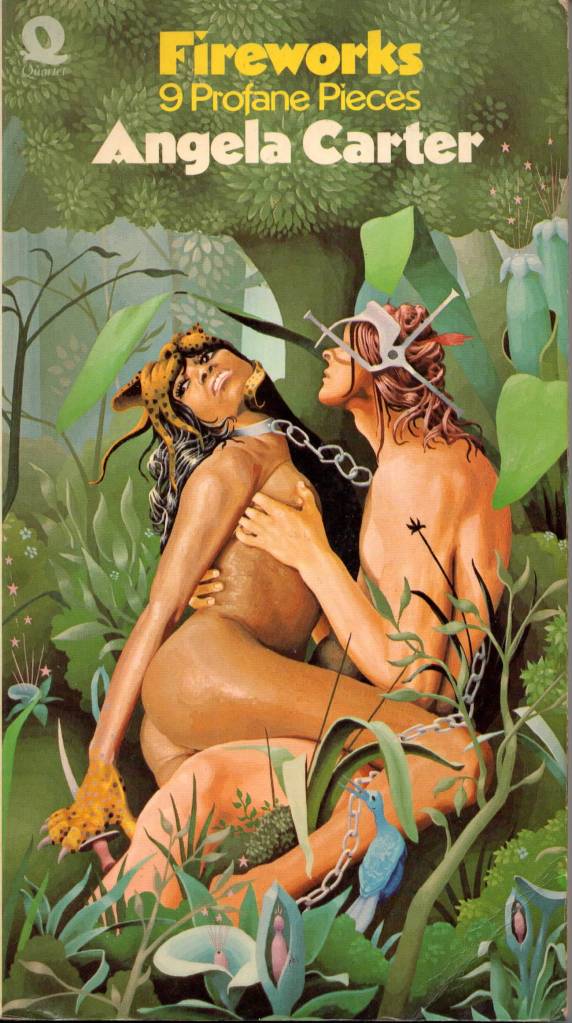

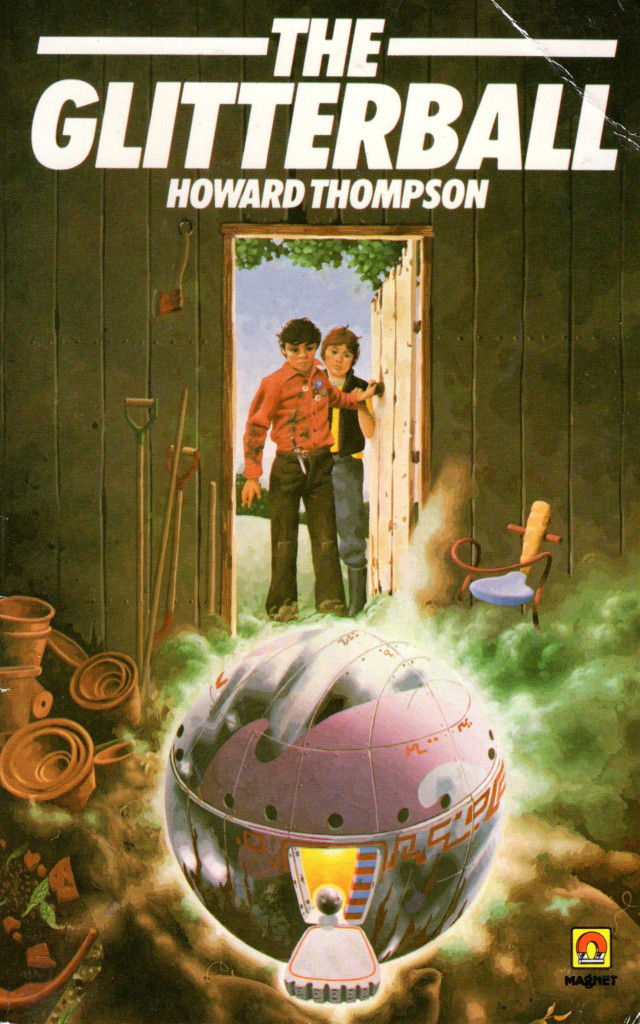

Even among the plethora of gifted artists working in the field at the time—particularly the stable of his peers at art agency Young Artists, which included Les Edwards, John Harris, Colin Hay and Peter Elson—Fowke’s vision stood out, at once playful and disconcertingly strange. Once aware of him, I started noticing his work all over the place: on Angela Carter books, on the cover of Nicholas Fisk’s great juvenile SF gem Flamers in the library, and in 1980’s faux galactic travelogue coffee-table book Tour of the Universe.

So sincere thanks to Bob for agreeing to be interviewed, and to his wife Pinney for being the trigger for it happening. Please visit www.bobfowke.co.uk to learn more about him and see more of his work. All of the images used in this article are © Bob Fowke, with all rights reserved by Mr. Fowke.

* * *

MCKENNA: Bob, could you please tell us something about how you originally became interested in art and about your training?

MCKENNA: Bob, could you please tell us something about how you originally became interested in art and about your training?

FOWKE: I’ve always been interested in art—I’m hardly alone in that—but perhaps no more than in literature and some other subjects. After school, I completed a foundation art course at Eastbourne College of Art, but I was more determined to learn the craft of painting than I was ambitious to be an “artist,” whatever that meant at that time. I would have preferred an apprentice system such as artists received in the Renaissance period. With this in mind, I went to Taunton College where I was able to study the craft of illustration under John Raynes, a well-known commercial artist of the 1950s/60s. His style is completely different to mine, but his discipline and the opportunity to watch a very competent professional artist at work were invaluable.

MCKENNA: How did you first find yourself involved in book jacket illustration?

FOWKE: Given that my work is, I hope, imaginative, book jackets, which are advertisements for products of the imagination, were by their nature where I would be at home and where I could get commissions. I painted some record sleeves and adverts, but book jackets were my bread and butter.

MCKENNA: Did you have any interest in the science fiction and fantasy genres before you began working in the field?

FOWKE: Perhaps sci-fi attracts young men because it tends to privilege concepts and plot over emotion, even if the best sci-fi writers often encompass emotion as well. So, I read science fiction/fantasy as an adolescent but as part of wider reading.

MCKENNA: How did you become involved with Young Artists and what were your experiences working with them?

FOWKE: On leaving Taunton, I sent some sample paintings to Young Artists, a remarkable illustrators’ agency of that period, and they were accepted immediately; I was fortunate that there was no period when I was searching for work. The images I sent were completely off the wall but John Spencer, who started the agency, saw something in them despite them being a bit mad. It was very good luck, and very kind of him to see something in my work.

Young Artists were wonderful. We illustrators were scattered all round the country because we could work anywhere, and there was a wonderful party once a year, held in their warehouse offices in Camden town, when we all descended from our scattered studios in the provinces and elsewhere. They were a great agency to work with and, as it turns out, quite historically significant.

MCKENNA: What are your memories of working in that period? Which of the projects you worked on were most memorable and why?

FOWKE: I moved to Shrewsbury with my young family and worked hard, putting my finished artwork on “red star,” a same-day delivery service by train to London. In my case there was a sort-of tri-weekly turnover of work I should say. There were no personal computers, no fax even.

There were so many projects, I can’t say which was most memorable. Perhaps it was painting the little dinosaur cards that went in Kellogg’s cereal packets, although not for artistic reasons. The artwork was very small and I worked so many hours each day that my eyes grew weak until, by the end, it took five 100-watt bulbs directed at the artboard for me to be able to see what I was painting. The eyes recovered, fortunately.

MCKENNA: Which artists—or films, authors, musicians, etc.—have exerted the biggest influence on you over the course of your career, and are they the same ones you find compelling now?

FOWKE: My tastes are boringly similar to a lot of people’s. To name but a few: Mozart and Beethoven, Samuel Palmer, Bosch, Constable. There’s a reason why these people are so famous.

MCKENNA: At least to me, your artwork seems to inhabit a space where Renaissance and surrealist visual sensibilities bleed into one another to create something that evokes both, but which feels very much like its own thing. Am I way off the mark?

FOWKE: You’re spot on. When I started painting book jackets I was especially influenced by Lucas Cranach and Albrecht Durer and some of the Italians, as well as by Magritte and the surrealists—-but I attempted to use their visual language to create a subjective reality of my own.

MCKENNA: You did your foundation at Eastbourne School of Art. Do you think that growing up on the South Coast of England informed your art?

FOWKE: I was brought up in Brighton and attended Marlborough College, then Brighton and Hove Grammar School, as it then was. Like most artists, I’m always influenced by the landscape around me, and in those days it was the South Downs, but I doubt the influence goes beyond that.

MCKENNA: How do you typically approach the composition of a piece?

FOWKE: Pencil, paper and free-association first, then work into it.

MCKENNA: I have the impression that your work has perhaps been a bit neglected because it’s somewhat less literal in its visions than some of your contemporaries. Would you say that’s a fair judgement?

FOWKE: I think you’re right. I wanted to paint my own subjective visions and those are things that are hard to pin down—-and who’s to say if they’re always what other people want—-if they don’t fit neatly into a particular genre.

MCKENNA: When and why did you begin to move out of illustration and into publishing?

FOWKE: It’s a very solitary occupation and at a certain point I needed others around me. Then, of course, I took up writing and that’s also solitary. A fool is a fool is a fool!

MCKENNA: What are you up to nowadays? And are you still painting?

FOWKE: I live in South Shropshire and I’m still painting and writing as well as helping others publish their books through YouCaxton Publications. There’s a lot to do.

MCKENNA: Is there a project that you’d like to paint but have never yet managed to get around to?

FOWKE: Several projects.

MCKENNA: Is there one painting of yours that you think represents particularly well what you wanted to accomplish with your art?

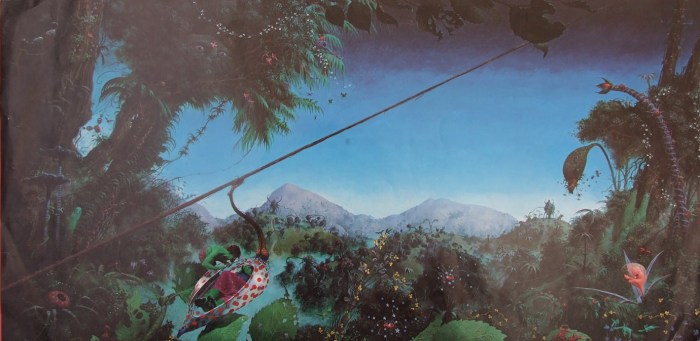

FOWKE: If I were to select a “Desert-Island” painting, I would choose one of the three I painted in India in 1980 for Alien Landscapes. I had a lot of time for each one and the level of detail in those paintings, if I say so myself, is exceptional; you need a magnifying glass to really appreciate them. I was illustrating Brian Aldiss’s story Hothouse, which involves a tree that covers the world, and for the first painting I took a room at the Theosophical Society in Chennai, which has one of the world’s largest banyan trees in its grounds. I ended up painting a small square of ground at its feet and no tree in the painting—a long way to go for a small square of ground but such are the workings of the subconscious.

MCKENNA: And finally: if you could pick any painting by any artist to hang in your otherworldly residence, what would it be and why?

FOWKE: Right now I would go for a Fragonard, The Swing obviously, or a Boucher, or even a ceiling by Tiepolo. In fact the ceiling would be the best value because I would get more of it. I love the exuberance and optimism of the Rococo style. But I might change my mind tomorrow.

![]() Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being one day rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being one day rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.